|

||

|

This blog never represents any organisation. This is a space where you will find the PEN News around the globe. This space is also used to circulate the urgent message from any PEN center over this world. I believe in FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION and I use this space for this purpose. I am a stark activist of International PEN and I follow it. All the news and articles are posted by Albert Ashok, and maintained by his pocket money, Your co-operation is welcome

Tuesday, January 24, 2012

English PEN warns Leveson against state regulation

Muslim organizations file cases against authors who read from Rushdie's book

source : Times of India

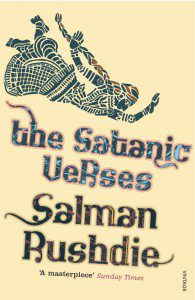

JAIPUR: After the police complaints lodged a day earlier, at least half-a-dozen court cases have been filed against four authors and three organisers of the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) where extracts from Salman Rushdie's banned book 'The Satanic Verses' were publicly read on January 20.

In Jaipur, five complaints have been filed by different individuals and organizations, including the All India Milli Council and the BJP minority cell, in a lower court demanding action against four authors Hari Kunzru, Amitava Kumar, Jeet Thayil and Ruchir Joshi and festival organizers Sanjoy Roy, Namita Gokhale, William Dalrymple.

Four of the complaints in Jaipur are scheduled to be heard by different courts on Tuesday, while the Milli Council's case is slated for a hearing on January 30. The case in Ajmer court by an individual allegedly linked to the ruling Congress party would be heard on January 25.

"We did not know that Rushdie would be participating at the literary event through video conferencing, otherwise we would have requested the court to order a stay on this too," the Mili Council secretary Abdul Latif told TOI on Monday.

The Council has sought action under various sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). "The book is banned in India so, legally, the authors cannot even read from it at a public event," Latif said. "We have sought action under IPC sections 153, 153A, 295, 295A, 298, 505, 504 and 120B," he added.

IPC Section 153 involves prosecution for wantonly giving provocation with intent to cause riot, Section 153A relates to punishment for promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, Section 295A pertains to deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious covers beliefs and Section 298 is invoked for uttering words with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person.

"A series of complaints have been filed in separate courts, including five at Jaipur and one at Ajmer against the authors and organizers. One complaint at Jaipur is by the BJP minority cell's Daulat Khan and the one at Ajmer by Muzaffar Bharti, who represents a local group, is a primary member of the Congress," alleged Kavita Srivastava, the civil rights organization PUCL's secretary.

The hardliner Muslim organizations and community leaders have been opposing Rushdie's participation in the literary event this year even though the author attended it as one of the speakers in 2007. The Muslim community protestors maintain that Rushdie's book has hurt its religious sentiments.

Source : Times of India

Muslim organizations file cases against authors who read from Rushdie's book

Bhanu Pratap Singh, TNN | Jan 24, 2012,JAIPUR: After the police complaints lodged a day earlier, at least half-a-dozen court cases have been filed against four authors and three organisers of the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) where extracts from Salman Rushdie's banned book 'The Satanic Verses' were publicly read on January 20.

In Jaipur, five complaints have been filed by different individuals and organizations, including the All India Milli Council and the BJP minority cell, in a lower court demanding action against four authors Hari Kunzru, Amitava Kumar, Jeet Thayil and Ruchir Joshi and festival organizers Sanjoy Roy, Namita Gokhale, William Dalrymple.

Four of the complaints in Jaipur are scheduled to be heard by different courts on Tuesday, while the Milli Council's case is slated for a hearing on January 30. The case in Ajmer court by an individual allegedly linked to the ruling Congress party would be heard on January 25.

"We did not know that Rushdie would be participating at the literary event through video conferencing, otherwise we would have requested the court to order a stay on this too," the Mili Council secretary Abdul Latif told TOI on Monday.

The Council has sought action under various sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). "The book is banned in India so, legally, the authors cannot even read from it at a public event," Latif said. "We have sought action under IPC sections 153, 153A, 295, 295A, 298, 505, 504 and 120B," he added.

IPC Section 153 involves prosecution for wantonly giving provocation with intent to cause riot, Section 153A relates to punishment for promoting enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, Section 295A pertains to deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious covers beliefs and Section 298 is invoked for uttering words with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person.

"A series of complaints have been filed in separate courts, including five at Jaipur and one at Ajmer against the authors and organizers. One complaint at Jaipur is by the BJP minority cell's Daulat Khan and the one at Ajmer by Muzaffar Bharti, who represents a local group, is a primary member of the Congress," alleged Kavita Srivastava, the civil rights organization PUCL's secretary.

The hardliner Muslim organizations and community leaders have been opposing Rushdie's participation in the literary event this year even though the author attended it as one of the speakers in 2007. The Muslim community protestors maintain that Rushdie's book has hurt its religious sentiments.

Source : Times of India

Monday, January 23, 2012

English PEN statement of solidarity with Jaipur authors

English PEN statement of solidarity with Jaipur authors |

|

||

|

Saturday, January 21, 2012

An annual report 2011: The PEN community in West Bengal, India

An annual report 2011: The PEN community in West Bengal, India

22nd Jan 2012

The PEN West Bengal together with

BudhBikel (Wednesday Afternoon) has been holding as usual weekly sittings with

rendering of literary contributions and discussion.

On 26 01 2011 The PEN, West Bengal had arranged a literary programme in

the A/C hall of the Kolkata bookfair

organized by the Publishers and Bookselleres Guild. Many poets and

literary personal, besides the members of the PEN participated to make the

programme success.

The Annual literary Evening of the PEN West Bengal was arranged on 25.04

2011 in the hall of Bangla Academy. Eminent poets and literary personal

attended and participated the programme which was presided by Sri Sunil

Gangopadhyay, Chairman of the PEN West Bengal.

A general body meeting of the PEN West Bengal was arranged on 21 08 2011

at the Theosophical Society Hall. It was

attended by the members in large numbers. The following agenda were discussed.

1.Accounts 2. Membership 3. Publication of the annual literary volume 4.

Election of the new excutive committee members 5. Annual literary awards 6.

Miscellanious

The PEN West Bengal organized a programme on 09. 09. 2011. In the Jibananda Hall of Bangla

Academy where in The Nilima Gupta memorial award for theatre was awarded. To

Smt Usha Ganguly an eminent person of the theatrical world of Kolkata Nilima Gupta memorial

lecture was delivered by Dr. Anirban Roy Chowdhury.

The PEN Westbengal Arranged an

excursion to Digha, on 23. 09 . 2011. On the occasion a literary session on 24

09. 2011 was also arranged which was chaired by Sri Surojit Dasgupta, executive

chairman of PEN. And Fajlul Alam, a well known writer from Bangladesh was

honoured in the programme. He was also the chief guest. The excursion ended on

25.09.2011

Besides members of the PEN West Bengal assembled in the house of Sri

Nisith Roy chowdhury on 18. 08.11 and 05. 10.11 and arranged a literary

programme as usual. We, PEN community in

West Bengal visit any place or join any literary event anywhere in India if any

organization or individual expresses a sponsorship.

Albert Ashok

Spl. and communication executive

9330858536

Kolkata

January 12 letter from John Ralston Saul, International President

News: Monthly letter from John Ralston Saul, International President – January 2012

January 18, 2012Dear friends, Dear PEN members,

A few days from now a large delegation – ten of us – will go to Mexico City. This will be a strong expression of solidarity for Mexican writers and journalists. It will also be unprecedented, with the entire Executive going – Hori Takeaki, Eric Lax and myself – as well as the Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee – Marian Botsford Fraser – and representatives of all four North American Centres, as well as the English and Japanese, all going to stand in public with our Mexican colleagues. Émile Martel, Russell Banks, Adrienne Clarkson, Gillian Slovo, Larry Siems and Adam Somers, as well as Renu Mandhane, head of the International Human Rights Program of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law, will join the Executive.

We will be working with the three Mexican PEN Centres – Mexico, Guadalajara and San Miguel Allende. The culmination of this will be a public event organized by Jennifer Clement, President of PEN Mexico, and her members, involving the delegation and some 50 Mexican writers on Sunday, January 29.

There is also a public letter of solidarity to Mexican writers which I hope you will all sign. It is coming to you separately.

This is not a delegation of experts. It is a delegation of writers using our public voice. And what we do and say will be quickly transmitted to you in the hope that you will respond in your own countries.

This is all part of a sustained Mexican PEN campaign. Recently the Day of the Dead initiative initiated by Jens Lohman of Danish PEN and Tony Cohan of San Miguel PEN, spread our concerns about the threats faced by Mexican journalists throughout our membership. We hope that these new Mexican initiative will take on our campaign a stage further.

A lot of you are already sending material to the new website. This is what we need: Centres all over the world telling the rest of PEN about their work and their risks. Please contribute.

Finally, these last few weeks have been moving and historically important for Czech writers and for the belief in freedom of expression that all of us have. First, our former President, Jiří Gruša, one of the leading dissident writers of the post war period died. Then Václav Havel, about whom a great deal has rightly been written around the world. Then Ivan Jirous, whom Paul Wilson called the “leader of the Cultural Opposition”. Jirous was a poet, essayist and leader of the psychedelic rock band Plastic People of the Universe. The struggle to get him out of prison in part inspired the Chapter 77 movement. And finally, Josef Škvorecký has died, another great writer and leading dissident. Living in exile in Toronto he created 68 Publishers in 1971 and for two decades published banned Czech and Slovak writers. The books then made their way illegally back into Czechoslovakia. Of course, there are many more names, but when four courageous and inspired writers die almost together it should be marked as an important moment for all of us in PEN.

Best wishes,

John Ralston Sau

Friday, January 20, 2012

PEN Statement on Death Threat to Salman Rushdie

News: PEN Statement on Death Threat to Salman Rushdie

PEN International is appalled to learn that the author Salman Rushdie has once again been the subject of a death threat; we condemn this criminal attempt to silence an international exponent of free speech.Rushdie was warned of the threat to his life shortly before he was due to attend the Jaipur Literary Festival, Asia’s largest event of its kind. The author had intended to discuss one of his earlier novels, the Booker-prize winning Midnight’s Children. The threat caused Rushdie to withdraw from the festival.

A brief statement was issued by the writer explaining that he had been warned by intelligence sources that members of Mumbai’s criminal underworld had put a price on his head. He said that he was unwilling to risk appearing at the festival, where there would be some risk to his family and other festival attendees.

Rushdie was the victim of an infamous attack on free speech over the publication of his book The Satanic Verses (1988), when the Ayatollah Ruohollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death, forcing him to remain in hiding for many years.

Source: PEN

Thursday, January 19, 2012

17 January 2012

Article written by

Soutik Biswas

Delhi correspondent

Article written by

Soutik Biswas

Delhi correspondent

Muslim groups have protested against Mr Rushdie

Muslim groups have protested against Mr Rushdie

India swiftly banned Mr Rushdie's Satanic Verses in 1988 because some clerics said it had insulted Islam. (The author said he was "hurt and humiliated" by the decision.) Now Darul Uloom, a leading seminary, has kicked up a storm saying Mr Rushdie should not be allowed into the country.

Darul Uloom is based in Uttar Pradesh which is going to the polls next month. Several political parties have said they support the seminary's demand. None of them want to antagonise Muslims, who make up 18% of the state's voters. Hosting Mr Rushdie, many in the ruling Congress party privately believe, would hurt its prospects.

Predictably there's a Twitter storm over the developments.

Keeping Mr Rushdie out, says one tweet, is a "sign of an immature democracy".

There were angrier tweets aplenty. If Mr Rushdie doesn't turn up, it will be a reflection of "the slimy cowardice of the soft state bit". "This isn't a society... Not a democracy... But the biggest hypocrisy in the world !!!", screamed another. "Nothing remains untouched by politics... not even literature," tweeted an exasperated journalist.

All of this, unfortunately, appears to be true. India, say many, has become an opportunistically soft state, unwilling to make its writ run for narrow political and religious ends. Both Muslim and Hindu groups have been responsible for launching attacks on freedom of expression, with the state usually capitulating without offering any resistance, critics say. They also question whether members of these groups have actually read the works they are so quick to criticise.

India's record of protecting freedom of speech has been patchy. Hardline religious groups - sometimes supported by governments - have burnt books, vandalised paintings, threatened scholars, forced a painter into exile, and pressurised authorities to ban books and essays.

Many believe Mr Rushdie should make a point by turning up at the festival, and the organisers and book lovers should force the government to give him protection. A no-show would be another damning indictment of a country which never tires of advertising itself as the world's largest democracy. This is the time to stand up.

Source: BBC

Article written by

Soutik Biswas

Delhi correspondent

Article written by

Soutik Biswas

Delhi correspondent

Why Salman Rushdie should turn up at Jaipur festival

Muslim groups have protested against Mr Rushdie

Muslim groups have protested against Mr Rushdie

The uncertainty over Salman Rushdie's participation in the Jaipur Literature Festival following protests by an Islamic seminary has a sense of déjà vu about it.

To be sure, the 64-year-old author hasn't officially called

off his trip at the time of writing. The organisers say that he's not

turning up on the first day of the five-day festival, but have removed

his name from the list of speakers. Rajasthan Chief Minister Ashok

Gehlot has made it abundantly clear he would prefer Mr Rushdie to stay

away.India swiftly banned Mr Rushdie's Satanic Verses in 1988 because some clerics said it had insulted Islam. (The author said he was "hurt and humiliated" by the decision.) Now Darul Uloom, a leading seminary, has kicked up a storm saying Mr Rushdie should not be allowed into the country.

Darul Uloom is based in Uttar Pradesh which is going to the polls next month. Several political parties have said they support the seminary's demand. None of them want to antagonise Muslims, who make up 18% of the state's voters. Hosting Mr Rushdie, many in the ruling Congress party privately believe, would hurt its prospects.

Predictably there's a Twitter storm over the developments.

Keeping Mr Rushdie out, says one tweet, is a "sign of an immature democracy".

There were angrier tweets aplenty. If Mr Rushdie doesn't turn up, it will be a reflection of "the slimy cowardice of the soft state bit". "This isn't a society... Not a democracy... But the biggest hypocrisy in the world !!!", screamed another. "Nothing remains untouched by politics... not even literature," tweeted an exasperated journalist.

All of this, unfortunately, appears to be true. India, say many, has become an opportunistically soft state, unwilling to make its writ run for narrow political and religious ends. Both Muslim and Hindu groups have been responsible for launching attacks on freedom of expression, with the state usually capitulating without offering any resistance, critics say. They also question whether members of these groups have actually read the works they are so quick to criticise.

India's record of protecting freedom of speech has been patchy. Hardline religious groups - sometimes supported by governments - have burnt books, vandalised paintings, threatened scholars, forced a painter into exile, and pressurised authorities to ban books and essays.

Many believe Mr Rushdie should make a point by turning up at the festival, and the organisers and book lovers should force the government to give him protection. A no-show would be another damning indictment of a country which never tires of advertising itself as the world's largest democracy. This is the time to stand up.

Source: BBC

[English PEN] Protect Salman Rushdie at the Jaipur Literary Festival

|

|||

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

সোফিয়া ওয়াদিয়াঃ ভারতীয় পি ই এন প্রতিষ্ঠাতা

ভারতীয় পি ই এন প্রতিষ্ঠাতা সোফিয়া ওয়াদিয়াকে আমরা অনেক ভারতীয়রাই চিনিনা জানিনা। তার কিছু পরিচিত এখানে আমি দিলাম। তিনি ভারতীয় সাহিত্যের...

-

‘পি. ই. এন. এর মা’ ও পেনের জন্ম কথা ‘পি. ই. এন. এর মা’ You can read also http://penwestbengal.blogspot.in/2009/04/history-of-pen-i...

-

ভারতীয় পি ই এন প্রতিষ্ঠাতা সোফিয়া ওয়াদিয়াকে আমরা অনেক ভারতীয়রাই চিনিনা জানিনা। তার কিছু পরিচিত এখানে আমি দিলাম। তিনি ভারতীয় সাহিত্যের...

-

Click the bengali writing image to see enlarged form this is a page from a periodical (above) underlined lines are wrong information about P...